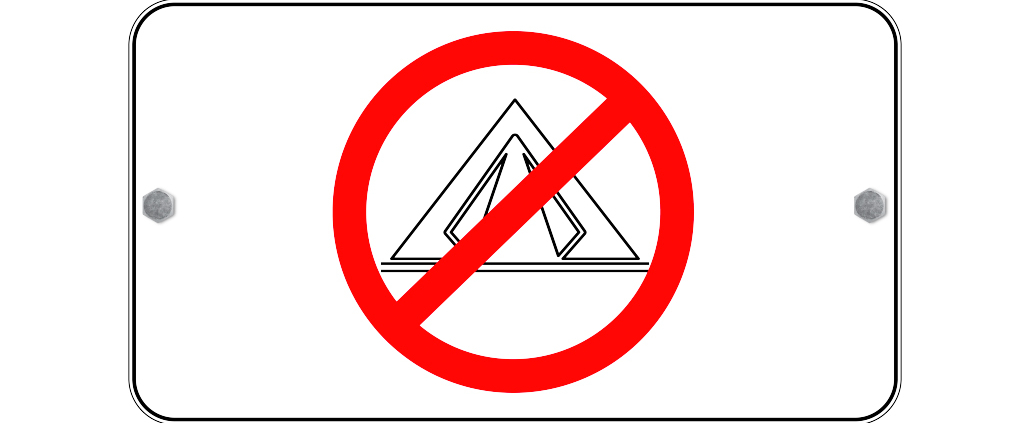

Portland’s daytime camping ban lacks concrete plans, procedures

Originally published on Streetroots.org

Written by Jeremiah Hayden, Sr Intern

Read full article

Vague communication from city causes concern among homeless Portlanders and service providers

Portland’s ‘daytime camping ban’ went into effect July 7, but the city has not communicated a rollout timeline, a map of allowed sleeping spots or when exactly Portland police will begin enforcing the ordinance, which includes fines and jail time. The ordinance amended city code to place new restrictions on when, where and how homeless Portlanders can shelter, including a ban on acts construed as “establishing or maintaining a temporary place to live” between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. and prohibiting “establishing or maintaining a temporary place to live” at any time on sidewalks, in parks and other public property. The revised code allows for two warnings before police can arrest a homeless Portlander, who will then be subject to a $100 fine, 30 days in jail, or both.

The city has not communicated timelines because, according to the city, it has yet to finalize — and in some cases begin — concrete plans and procedures for outreach to homeless Portlanders, enforcement training for PPB officers, or collaboration with service providers and county partners.

Local service providers say the lack of communication poses additional challenges and has heightened the level of concern for the people they serve.

“The general sense from our community of guests here is that there is anxiety around the unknowns,” Katie O’Brien, Rose Haven executive director, said.

According to O’Brien, the day shelter serves more than 3,000 people each year, providing food, clothing, showers and community for women, children and people of marginalized genders. Organizations like Rose Haven are also the first point of contact for people who need vital information about shelter during extreme weather events, healthcare access or how to navigate city policy.

“We’re where people come for information because they trust us,” O’Brien said. Thus far, the city’s communication about the ordinance is scattershot. The ambiguity creates new anxieties for homeless Portlanders and squanders an opportunity for service providers to disseminate reliable Information.

As it stands, the ordinance’s 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. time restrictions create new concerns about when and where people will be able to sleep. Many queer, trans and female identifying people sleep during the day because they feel unsafe sleeping in public at night, and some work at night so they can sleep in relative safety during the day.

“That is definitely on the minds of folks that have that sort of lifestyle for safety reasons,” O’Brien said. “We do have some people who will come here and lay on a couch for a few hours and try and get some rest here because they feel safe here.”

The new restrictions create additional difficulties for people with disabilities who, when enforcement begins, are required to break down, pack up and haul all sleeping materials each day. If they are unable to pack up, people could face fines, jail time and the immediate seizure of their Property.

In O’Brien’s case, she said she had to proactively contact the mayor’s office to be able to offer input on the ordinance.

O’Brien said she immediately initiated a conversation with the city when she first heard about the proposal from other service providers, and met with Wheeler’s senior policy advisor Skyler Brocker-Knapp the day before Wheeler introduced his proposal in a May 31 City Council meeting. O’Brien met with city officials twice, but remains frustrated by a lack of clarity around where people can sleep, keep their belongings when they want to access services and how Rose Haven should direct people who depend on them for vital Information.

The requirement to carry belongings throughout the day also poses new challenges for service providers like Rose Haven. According to O’Brien, the shelter currently serves around 150 people per day, and she expects that number to rise when the ban goes into effect. An increase in carried possessions means limited space is used as storage rather than a place to offer services. “If people have to pack up their lives and bring them in with them, it changes my capacity,” she said. “I can actually serve less people.”

In light of the new ordinance, Rose Haven already had to pivot toward addressing more basic needs in the moment rather than focusing on stabilizing solutions like connecting people to recovery, housing and employment. Trauma-informed care means providers focus on addressing basic needs before attempting to solve long-term issues.

“This disrupts all that because now we’re working on different things with people,” O’Brien said. “It works against our ability to help provide support in those ways because now we’re just helping people move stuff around.”

O’Brien remains optimistic about the ongoing conversations, despite slow Progress. “I hold hope that we will have some collaboration because we need it,” O’Brien said. “But what I also want to say is, we need it for what we’re doing right now.” Gardner said Do Good participants are concerned about the additional strain that will be placed on daytime resource providers who are working at their threshold.